Ice Breakers: Telling Canadian Stories

Originally posted: April 14, 2020

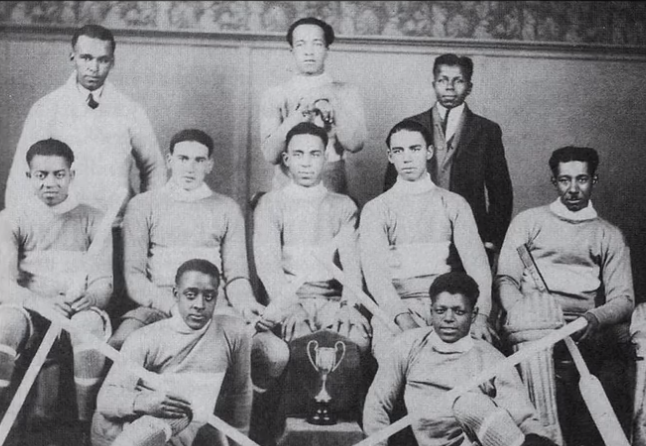

Still from Ice Breakers Documentary

My family has been home, physically distancing to protect our community, and to flatten the curve on COIVD-19 since March 13th. Officially into our second month of this new life rhythm, I continue to make peace with the fact that my client-load has shrunk (so much of my work is about community-building, coaching, and education), that I rarely get time alone, that I am the head chef at home (ok, I do love getting my bake on), and that I’m a teacher/learning facilitator to my two littles (very different than parenting). The blessing in the last one is that I’ve come to appreciate this access I now have to a deeper curiousity.

In my quest to have a broad range of stories, narratives, and mediums to facilitate learning with my children, I’ve been researching different websites and building a list of awesome resourcecs to reference in the coming months. One website I’ve been spending a lot of time on is the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) website. I’ve always been a fan of documentaries. I used to live in Toronto and I loved going to the Hot Docs festival. I relished the gift of being able to throw myself into diverse stories about communities I knew little about, places I had yet to visit, and ways of the world that were still unknown to me. Ultimately, I think my love of documentaries stems from this effort to understand and appreciate the diverse expression of human experience, and to celebrate just how much we all have in common as a human race.

A few nights ago, I was browsing through documentaries on the NFB website, and I came across a Canadian documentary short called Ice Breakers (2019), by Sandamini Rankaduwa. Rankaduwa is a Maritime Sri Lankan-Canadian writer (Rankaduwa was a 2018 BuzzFeed Emerging Writers Fellow), comedian, and film maker.

Ice Breakers brings to light the buried history and contributions of a Black hockey league in Atlantic Canada. Rankaduwa does a great job of weaving the rise of Cole Harbour hockey player Josh Crooks,a young, Black Canadian currently playing for the Halifax Macs, into the narration of the history of the Coloured Hockey League of the Maritimes.

In a sport where Black players like Josh continue to be chronically underrepresented, over the course of this documentary, we see Josh discover that his unshakable passion is tied to a profound and extraordinary heritage.

“It’s an important part of our history; it’s part of Canadian history, hockey history, and something that we should be proud of, but we know so little about it, if anything,” says [Rankaduwa], writer and stand-up comedian during a break in editing at her part-time home in Brooklyn.

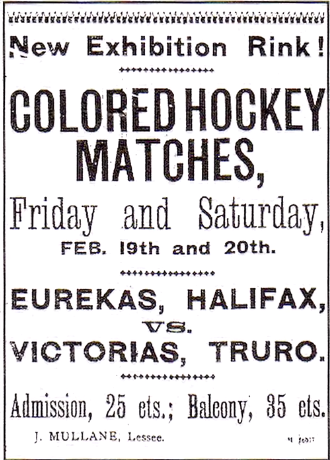

Rankaduwa’s documentary was inspired by the book Black Ice: The Lost History of the Coloured Hockey League of the Maritimes, 1895-1925 by George and Darril Fosty. The book details the league’s rise and eventual dissolution, with an East Coast circuit that included over a dozen teams and around 400 players at its peak.” (The Chronicle Herald, April 2019)

Still from Ice Breakers Documentary

What I appreciated most about this documentary is the way Rankaduwa skillfully centred the voices of those who were closest to the experience, representing different perspectives, that contribute to a broader understanding of the story. We got to hear from Josh, Josh’s father, who got emotional, at times, recounting the racism and abuse his son experienced on his hockey journey, and Leland (Lee) Francis, hockey coach and vice-president of the Black Ice Hockey and Sports Hall of Fame Society.

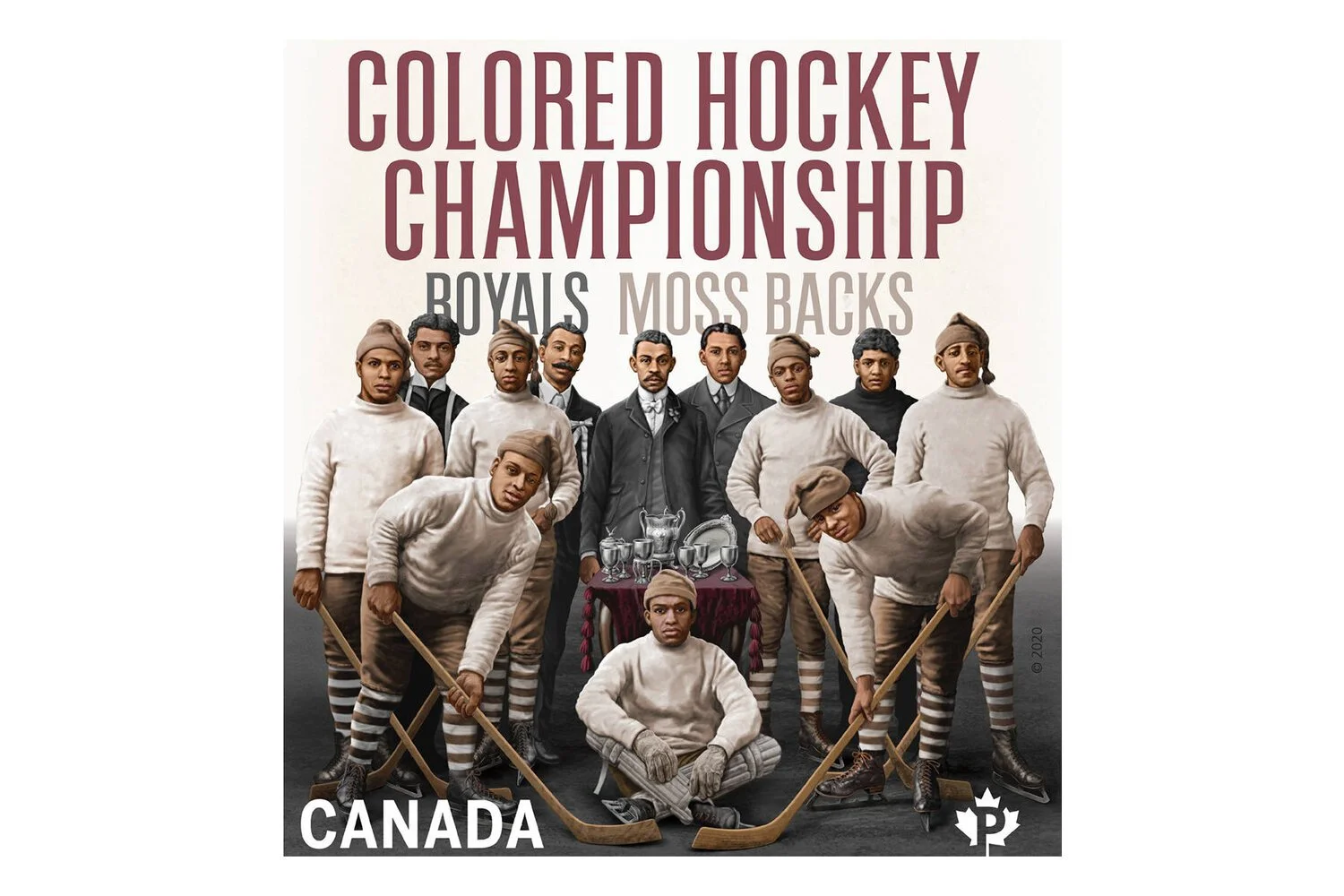

From Canada Post Magazine website

Canada Post released a commemorative stamp earlier this year celebrating the achievements of the league (founded 22 years before the NHL) and the contribution of the Black community to the sport of hockey. This was the first time I had heard of this league, and that hockey had roots in the Black community.

“The story begins in the late 1800’s with Baptist Church leaders who believed all-Black hockey would be a great way to attract young Black men to the Church to strengthen their religious path. They were also painfully aware that Black players were restricted from playing in white-only leagues. Black players possessed skills that rivaled the players in “white-only” leagues. Their style of play was physical, fast and innovative. Players pioneered certain aspects of the game as we know it today, such as the down-to-the-ice style of goal-tending, or butterfly style.” (Canada Post Magazine, Feb 2020)

It’s important to share stories like these because they help us to unravel the thread of Canadian narrative that centres dominant White Canada as the creator of all things “Canadian.” Hockey, for many, is as Canadian as you can get.

“Historically, white Canadians have made up the bulk of NHL players. While the NHL has become truly international since the end of the Cold War, about 50% of its players are still Canadian. Influential members of the hockey media, like Don Cherry [finally fired from CBC in response to racist remarks in 2019] and Bob MacKenzie, are Canadian. Canadian politicians, fast food companies, artists, and beer commercials have worked for years to equate hockey with White Canadian identity -- and it's worked. Hockey culture and White Canadian culture are synonymous.” (Victory Press, 2017)

And yet, over the last two decades, the face of the NHL, and Canadian Hockey, has changed, is changing, to reflect the faces of our nation. Conversations about making the game more inclusive are being driven by champions like Damon Kwame Mason, who directed, produced, and wrote the 2016 documentary Soul on Ice:

“It takes me back to when I was a child, and I loved hockey, my favourite hockey player was Guy Lafleur. When we would go outside and play road hockey, and everyone was picking their favourite player, I remember this one time I said “I’m Guy Lafleur” and a kid told me I can’t be Guy Lafleur because Guy Lafleur is White. I didn’t know that Mike Marson was out there, I didn’t know that Bill Riley was out there, I didn’t know that there was a guy by the name of Willy O’Ree, or Herb Carnegie that I could say I want to look up to. I think, as an industry, as broadcasters, as sports broadcasters, we have to also do a better job of showing everybody, because once we show everybody, then everybody feels included. We have to have an environment that’s also safe and welcoming….if you see someone that looks like you, then you know you can be a part of that as well.” (Sportsnet Interview, November 2019)

This begs the question; how many other pivotal Canadian stories have never made it to mainstream awareness? How many other “Canadian” stories do we tell ourselves that don’t actually reflect the diverse origins from which they came? How many young people, with innate talent for hockey, or other career paths, choose not to move forward because they don’t see themselves in the space? If a sport that has roots in the Black community that run more than a century deep, which, today, is still rife with racism, what needs to change?

Doing the work to educate ourselves is a good start. Once we begin to expand our own understanding of our history as a nation, and to realize that the history we do know has been written by hands that held the power to do so, we can begin making space in our minds, hearts, and consciousness, for the reality that revision is necessary for a more authentic history. A history that celebrates the diverse contributions of many founding cultures and pioneers who contributed to Canadian culture.

I’m grateful to the National Film Board of Canada for preserving, celebrating, and funding documentary work to capture the diverse histories and experiences (much which remains out of the realm of the mainstream) of Canadians. I talk about another documentary on NFB I enjoyed recently on this LinkedIn post, called Between: Living in the Hyphen (2005).

These are stories that need to be told in every elementary school and high school across Canada, in a way that authentically represents the experiences, the voices, the struggles, and the triumphs of diverse communities across Canada.

In a time where our interconnectedness is clearly undeniable, and the reality of how tightly our collective fates are interwoven is staring back at us in the mirror, what better time is there to dive deeper into the histories of diverse communities that contributed to, and continue to contribute to the Canada we enjoy today?