Making Space for Each Other

Originally written February 28th, 2023

The other day I was on my way to an appointment and during my drive, there was an unexpected lane closure and I had to merge into the lane on the right. Driver after driver passed as I tried to merge, one even glared at me as they raced past. Eventually, a driver slowed down and made space for me to merge. I merged into the lane and thanked them with the customary wave in the rear-view mirror.

The experience got me thinking about space. Our relationships to space, to time, and to each other.

In my work as an equity and inclusion consultant, facilitator, and coach, as well as in my work as a volunteer community mediator, holding space is a significant part of my work and practice, so much so that I would call it my superpower. I open most of my equity, inclusion and belonging capacity-building sessions with a set of practices that are called “setting the container”, which David Spinks defines as: the rules, expectations and intentions of an interaction so participants know how to make a quality contribution. My role often sees me holding space for conflict between people and groups, often in emotionally charged contexts, and for the possibility of tender shoots of ideas in their infancy, a new understanding and way of being emerging in communities, and most often, the unfurling of individual and community emotions, stories, and ways of seeing.

Natajsa Wagner, a Psychotherapist, defines holding space as:

“Our willingness and ability to be alongside someone in their experience of pain. Holding space means giving support that is free of judgment. It involves a conscious and deliberate choice to put aside our agenda, the need for our own specific outcome and the desire to give advice or “fix” a person or their situation.”

As I continued with my drive, I wondered about the people who rushed past me and did not stop to let me in.

What was their relationship to space?

Was the road theirs to own and good luck to anyone else who needed it?

Was the road a scarce resource that they needed to claim or else they would lose it?

What about their relationship to time?

Were they running late and needed to get to their destination at all costs?

Were they rushing to collect a sick child or family member?

What about their relationship to me?

Was I the total sum of a stranger to them?

Was I invisible to them?

Did they even pause to notice who was in the car?

Was there a recognition of the possibility that I could potentially meet them at the same destination?

What if I had been the Doctor tending to their ill family member that they were rushing to visit?

Or taking my child to the same dance class that they were taking theirs to, which would mean we’d face each other in the hallway of the dance studio?

What about our relationship as community members, drivers, or as fellow humans?

I thought especially of the driver who made the time to glare at me, and how easily they were unsettled at simply the sight of a fellow driver needing to enter the lane.

I then turned the flashlight of curiosity on my own practices because, after all, when we point one finger out at humanity, a few fingers are pointing back at us as well. I reflected on the times where I did not slow down or stop to make space for someone else to merge.

What was happening for me?

How did the impact of my choice affect the other driver?

Did I stop to consider my relationship to space?

To time?

To my fellow community members?

I must be honest that it was a firm no on most, if not all, of these questions, a lot of the time.

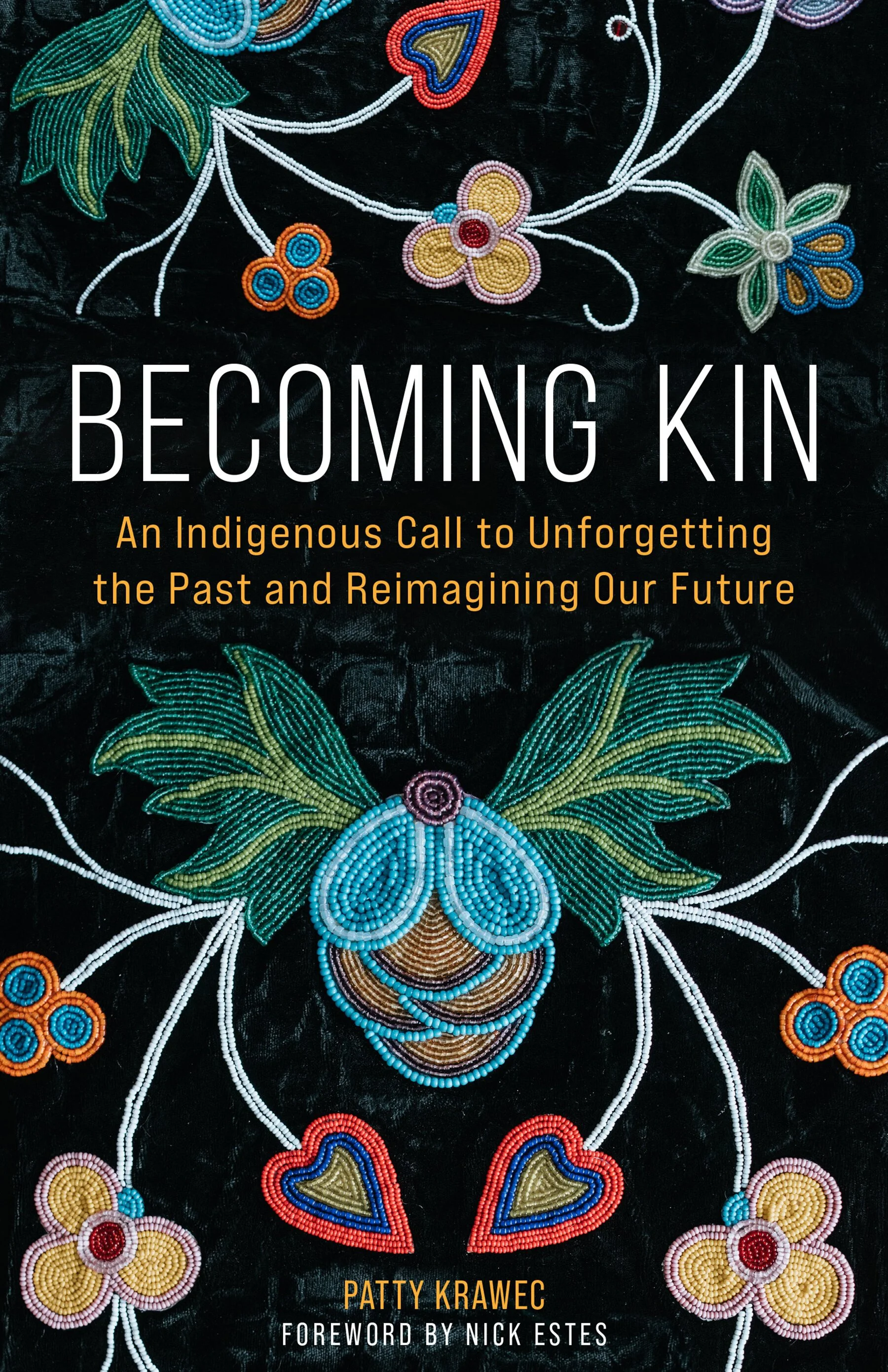

Niagara-based Patty Krawec, author of Becoming Kin: An Indigenous Call to Unforgetting the Past and Reimagining our Future and Podcaster, talks about the importance of considering one’s relationship to land, to Indigenous communities, to each other, to time and history. That “none of us are going anywhere and we need to learn how to be good relatives. You need to learn how to be good relatives”.

I considered my relationship to the road; is it my road? Was it made for me? Do I own it? Is it a doctrine of discovery situation where because I was there first so it’s mine?

Or is my relationship to the road one where I have the privilege of access to it? Is the road a shared resource for which we are all stewards? Is it a resource I get to use on the condition I share it? What rules, values, or principles am I following, beyond what I learned in my driver education course, as I consider my relationship and entitlement to the road and how I use it?

What would be different if we were active commitments to being good relatives to each other? To ourselves even?

I considered my relationship to time. It seems that, over time, my relationship to time has gotten more and more demanding. When I became a parent, the value of an hour, 30-minutes even changed drastically. The difference between my baby taking a 45-minute nap or a 90-minute nap was felt immensely, and often traumatically if I was trying to get some sleep too after a sleepless night, or trying to get a meal cooked for dinner before they awoke.

The pandemic actually helped me to re-calibrate my relationship to time because I had the privilege of being in a position where I could work from home, could have my kids in virtual school at home, and had the time to center our wellbeing and mental health.

These days, at least much of the time, I can actively challenge the story in my head that tells me that I never have enough time. Intentionally deciding to make time for the things I care about, to root my choices and actions in the things I am working to be an active commitment to is one way I have created a healthier relationship to time.

Lastly, I considered my relationship to fellow community members, which also includes drivers on the road. I consider myself a passionate community builder, having served as a volunteer since the age of 16, having organized street festivals and events in my neighbourhood, and having centred community wellbeing, equity and justice in most of my life’s work. The question is, how well was I living my commitment in my day-to-day life?

A few months ago, I was driving on the highway and reflected on the resentment that arose within me when a driver was coming off an on-ramp just ahead of me and needed to merge into my lane, or rather, the lane I was in. They had indicated with their signal, their intention to merge, as the rules of the road tell us to do, and I felt resentful that I had to slow down to let them in. I slowed down and let the person in, and they waved their hand to thank me.

I sat with the feeling and asked myself where that came from. I didn’t know the person I let in; their need to merge had nothing to do with anything I was doing or where I was going, the highway is for all of us to use and merging and leaving lanes is one of the key activities that take place on a highway.

I understood, in my mind, that their need to use the highway was no more or no less important than my need to use the highway, but somewhere in my body there was a disagreement about this fact. I continued to reflect on this as I drove, and I realized that there was a lie my ego had told me that I was buying into in an embodied way. That lie is that somehow, the world revolves around me and my needs, and that I own the road.

This was an aha moment for me, and I know that’s likely an obvious one to you, as you read this but somehow, there it was. According to psychologist Jean Piaget, children below the age of two years old think that the universe revolves around them. The only thing is that I am a 40-something adult driver and this idea no longer fits with the context.

The thing I have come to understand about holding space for others is that it starts with how well each of us, as individuals, holds space for ourselves. What is our personal relationship to space? Do we believe we deserve space? Do we believe others deserve space? Do we make space, with compassion, and empathy, for ourselves, our needs, our pain, our joy? After all, the degree to which we hold space for ourselves, our imperfections and our vulnerabilities, will determine the depth of container we become for others in the community.

Do we take space when it’s available? Do we move like we own all the space in a room? Do we drive like we own the road? Do we show up to social gatherings like all of the conversation should revolve around us? Are we even aware of how much space we are taking up and considering what is left for others? Do we take some space with an awareness and belief that we need to leave space for others?

So much of my work with communities, leaders, and organizations is also informed by adrienne maree brown's ideas of holding change, what she calls “the sacred way of facilitation and mediation.” This inherent belief that holding space, especially safe enough, accountable, and accessible space, makes so much more possible in community – innovation, healing, joy, understanding, solidarity, trust, and so much more.

I’ve often had a front-row seat to seeing the way community transforms when power, space, and time is shared in a way where we recognize that we each have a right to these resources. I've had the benefit of being in spaces held so tenderly, so equitably by facilitators and community process designers that, when I left, it was with a new found strong soul community, or where the experience actually helped me to see more of myself, to understand my place in a community journey, and grounded me in my relationship to others as a core need to create the communities we long for.

The next time you’re on the road, see if you can notice the way you either make space for, or don’t, for other drivers and consider how this reflects what you’re an active commitment to. And if you see a sun-shaped air freshener hanging from the rear-view mirror, then you just might be letting me in.